Is it true that the Bible can only be truly understood through a Jewish lens—the views to the rabbis who wrote the Talmud, Mishnah, etc? Some podcasts I'm listening to seem to be saying that everything I've learned about the Bible is either incomplete or incorrect. What do you say?

Well, yes, the Palestinian background is key for understanding the New Testament. This view was forcefully presented in the 1970s and accepted by most NT scholars. After all, not only Jesus but all his apostles were Jewish, and the OT was the Bible of the earliest Christians.

Well, yes, the Palestinian background is key for understanding the New Testament. This view was forcefully presented in the 1970s and accepted by most NT scholars. After all, not only Jesus but all his apostles were Jewish, and the OT was the Bible of the earliest Christians.

Yet there was a world of difference between Judaism in the time of Jesus—well before the Romans destroyed the Temple and effectively extinguished all Jewish sects apart from the Pharisees—and the post-70 AD Jewish world. Nearly all sources appealed to by those preaching a Jewish Christianity date from after the war with Rome, and it is likely there is a fair amount of retrojection going on. Idealization of the past and even eccentric opinions were claimed to accurately depict authentic Judaism. That is, the views of the rabbis in 200 AD or 500 AD are being read back into the record.

Yet it is not the case that our analysis of the New Testament should totally bypass the later Jewish compendia of tradition, as many of these do reflect more ancient ideas. We should not assume that just because a text was written in the 4th century that it only reflects 4th century ideas. However, this kind of comparative work has to be done fairly carefully. Simply reading these later traditions back into the New Testament is likely to throw up all kinds of false trails.

Jewish literature more contemporary with the New Testament—and less likely to lead us down false trails—would include the works of Josephus and Philo (both of whom lived in the first century), and the Old Testament Apocrypha (mainly 2nd and 1st century BC). Without having a sound grasp on this sort of literature, it is difficult to properly contextualize the New Testament. Of course that is very different from claiming that modern gentile believers are in any way beholden to the demands of the Torah.

Sources

For those unfamiliar with the ancient Jewish sources, the following terms may be helpful:

- Tanakh: the Old Testament, consisting of Torah (law), Nevi'im (prophets), and Kethuvim (writings). The same O.T. that most Bible-reading Christians use, although the order of the books is slightly different. Completed several centuries before Christ.

- Septuagint: the Greek Old Testament, translated in the 3rd-2nd centuries BC, so that the majority of Jews (no longer understanding Hebrew) would be able to read the Bible.

- Targum: Aramaic translations (literal or free) of the Hebrew O.T. books, dating to the second half of the 1st century, 2nd century AD, and later.

- Mishnah: The codification of the "oral law" (rabbinic traditions, as opposed to Torah), around 200 AD. Represents an idealized 2nd-century outlook.

- Midrash: Free commentaries on O.T. books (esp. the Torah), written from the 3rd century AD onwards.

- Tosefta: Collection of rules and comments dating to 3rd or 4th century AD.

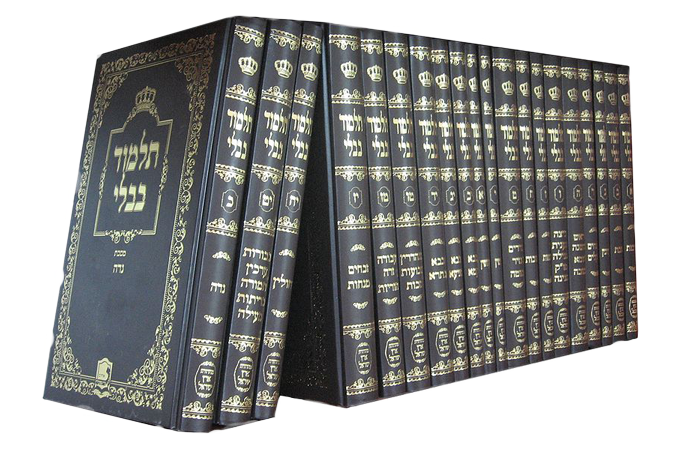

- Talmud: includes Mishnah and Gemara, which is an expounds Mishnah as well as various biblical passages and topics. This is the principal text of rabbinic Judaism today.

- Palestinian Talmud: lengthy Aramaic commentaries on the Mishnah, completed in the 5th century.

- Babylonian Talmud: dating to the 6th century and more influential than the shorter Palestinian Talmud. Contains the opinions of 1000s of rabbis, and fills over nearly 5500 pages.

As we can see, apart from the biblical books, all other sources date to many generations after the time of Christ. I have found many modern writers, especially those broadly falling into the "messianic" camp, to be speculative, weak on fact-checking, and seriously out of step with biblical scholarship.

As biblical scholar Raymond Brown put it:

"There is a major problem about the use of this Jewish material in NT work. Since almost all of it was committed to writing after the main NT books, to what extent may it be used to enlighten the accounts of Jesus' life and reflections on the early church? A number of scholars, assuming that the traditions in these and even later works reflect early Jewish thought, practice, and terminology, feel free to cite passages written down anywhere from 100 to 1000 years after the time of Jesus. Others (among whom I count myself) advocate extreme caution and want confirmation that what is being quoted was known before 70 AD" (An Introduction to the New Testament [New York, NY: Doubleday, 1996], 82-83).

"There is a major problem about the use of this Jewish material in NT work. Since almost all of it was committed to writing after the main NT books, to what extent may it be used to enlighten the accounts of Jesus' life and reflections on the early church? A number of scholars, assuming that the traditions in these and even later works reflect early Jewish thought, practice, and terminology, feel free to cite passages written down anywhere from 100 to 1000 years after the time of Jesus. Others (among whom I count myself) advocate extreme caution and want confirmation that what is being quoted was known before 70 AD" (An Introduction to the New Testament [New York, NY: Doubleday, 1996], 82-83).

Claims to reject:

So what are we to conclude? Although the relationship of the Old Testament to the New Testament is sometimes complex (I don't claim to have all the answers), there are several claims that do not hold water:

- That Torah is still somehow binding on Christians.

- That Jesus trained his disciples in the same way later rabbis (e.g. 400 AD) trained their disciples—like apprenticing young boys, requiring memorization of the whole Bible, and imitating the rabbi in multiple personal areas.

- That Mishnah and Talmud are the best lens for interpreting the O.T. and even Christianity itself.

- That in some sense physical (political) Israel has any special standing before God, or is in a covenant relationship with God.

- That Christians should use Hebrew-sounding terms and names (synagogue instead of church, Yeshua instead of Jesus, Adonia or HaShem instead of Yahweh, rabbi instead of preacher, etc).

- That some followers of Christ are Jewish, others Gentile.

- That "Jewish" disciples of Christ should follow Torah.

To be fair, the New Testament must certainly be understood through a Jewish lens, but that has to do with the fact that it was written by Jews (with the possible exception of Luke and Acts); Jesus was Jewish; their thought world was Jewish; and, naturally, the way in which the authors of the New Testament made sense of the events of the first Easter was through the thoroughly Jewish lens of the Hebrew Bible. So, in some sense, the answer to your question is yes—just not in the way some Bible students are teaching.

To be fair, the New Testament must certainly be understood through a Jewish lens, but that has to do with the fact that it was written by Jews (with the possible exception of Luke and Acts); Jesus was Jewish; their thought world was Jewish; and, naturally, the way in which the authors of the New Testament made sense of the events of the first Easter was through the thoroughly Jewish lens of the Hebrew Bible. So, in some sense, the answer to your question is yes—just not in the way some Bible students are teaching.

For more, please see my little book Messianic Judaism: Should Christians Follow the Old Testament?

(Special thanks to Andrew Boakye of Manchester University for his contributions to this article.)