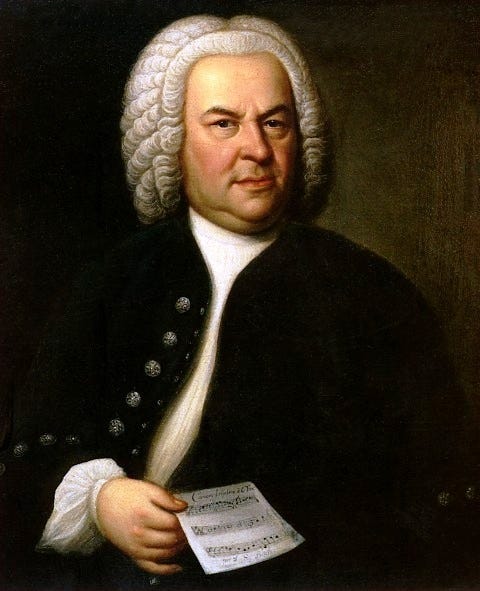

The Brilliance of J. S. Bach

My wife’s and my favorite composer is Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750). His music is brilliant, complex, and enthralling. We love his choral pieces in particular and his oratorios in general—along with his Orchestral Suites, his French Suites, the Brandenberg Concertos—well, the works! Did you know that Bach even wrote the playful Coffee Cantata?

Bach’s genius is evident in his display of counterpoint—multiple independent musical lines that are interwoven to create an exquisite harmony. You can check out a bit of this genius on YouTube—the brief visualized rendering of Bach’s “Crab Canon” from his Musical Offering (BWV 1079).[1] This is the musical parallel to the literary palindrome, which reads identically forward as well as backward—for example, “A man, a plan, a canal—Panama.” At any rate, this piece of music—in the form of a Möbius strip—begins simply and grows in complexity as it is played simultaneously from beginning to end and from end to beginning. Again, check it out on YouTube to experience through sound and sight how this complexity works.

Bach’s Spiritual Warmth and Devotion

Bach was not only a musical genius. He was also a theologically-informed and dedicated churchman in the Lutheran tradition—a tradition that followed the Augsburg Confession. Bach’s music combined with deep Lutheran piety has proven to be a stirring combination. The late atheist and paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould of Harvard was a Bach aficionado who sang in many a Bach cantata and also wrote the foreword to Bachanalia: The Essential Listener’s Guide to Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier. My Boston College philosopher friend Ronald Tacelli, S.J., with whom I coedited Jesus’ Resurrection: Fact or Figment? once lamented that he had come to discover Bach far too late in life. He expressed to me being overcome by both the exquisite music and warm devotion in Bach’s works.

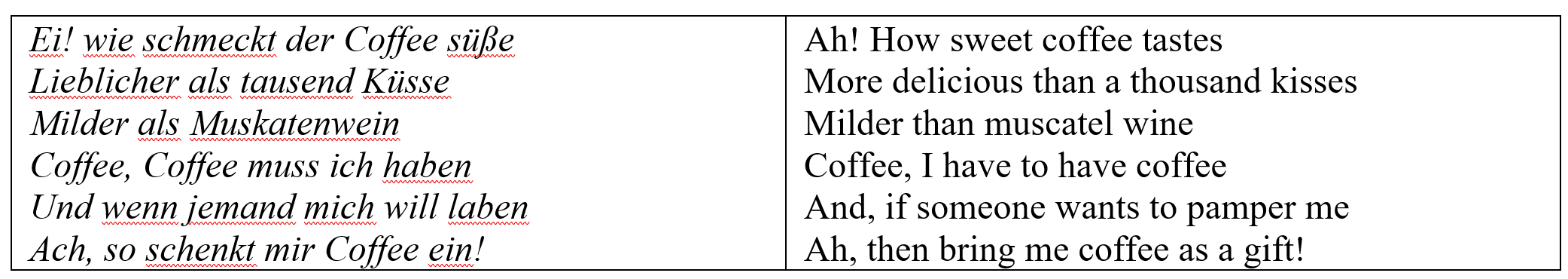

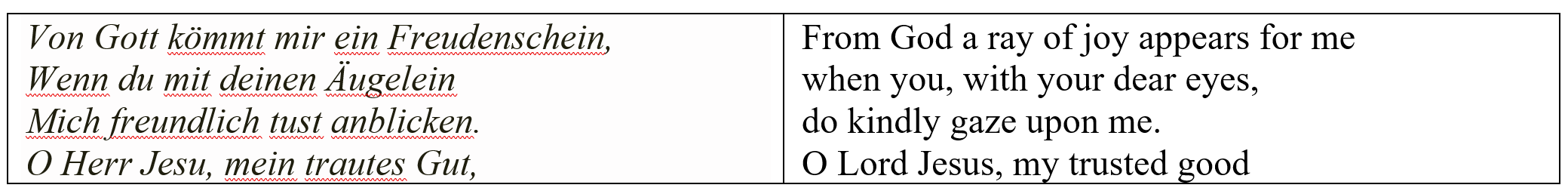

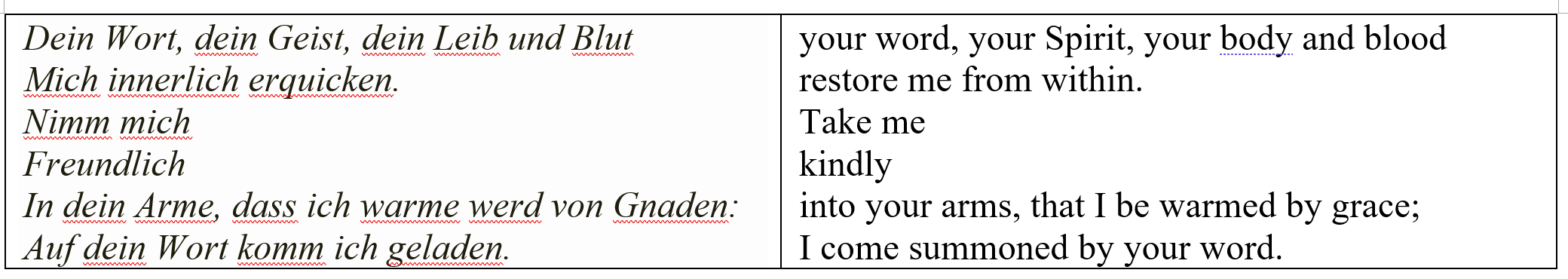

Let me give a few examples of my favorites. One choral piece (Von Gott kömmt mir ein Freudenschein from BWV 172) exudes warm devotion to Christ in deeply personal terms. (Just give a listen/watch on YouTube: start at around 16:21). For your convenience, I’ve provided the German libretto with English translation:

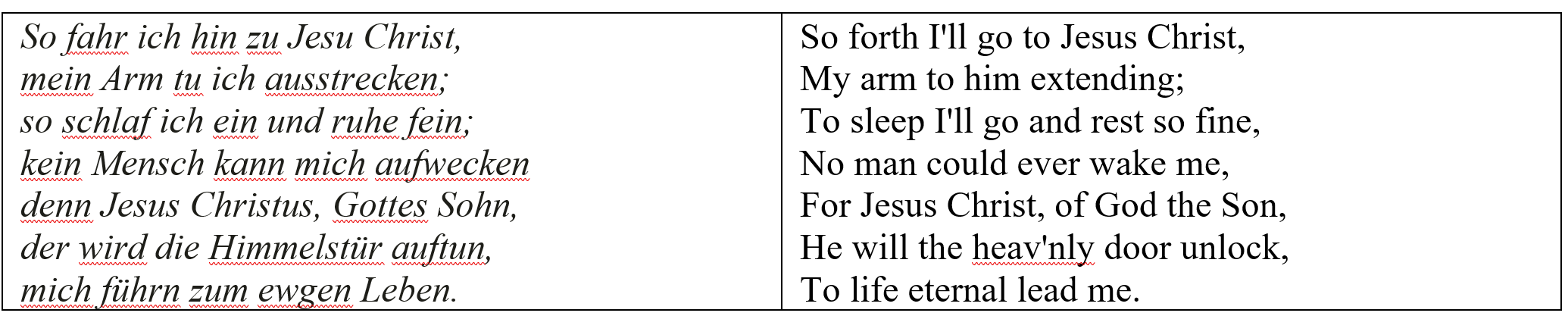

Another choral piece, So fahr ich hin zu Jesu Christ (“So I go to Jesus Christ” [from BWV 31]), expresses the believer’s confidence while dying, anticipating Jesus’s sweet heavenly embrace. Here is one rendition I very much like (with the Japanese conductor and Bach scholar Masaaki Suzuki conducting. However, this one has been my absolute favorite over the years; I so love the trumpet descant.

In case you weren’t aware, Bach’s music with its warm and deep spirituality has had a significant impact in Japan—a place that has no native word for hope, but many Japanese have found Bach to be an instrument of the Holy Spirit who inspires gospel hope.

Bach, the Fifth Evangelist

Over the decades, my wife and I have enjoyed listening to and reading the libretto of the St. Matthew Passion during Holy Week. Other rich Gospel-centered works by Bach include St. John Passion, the Mass in B Minor, and the jubilant Easter Oratorio. No wonder Bach has long been called “the fifth evangelist.”

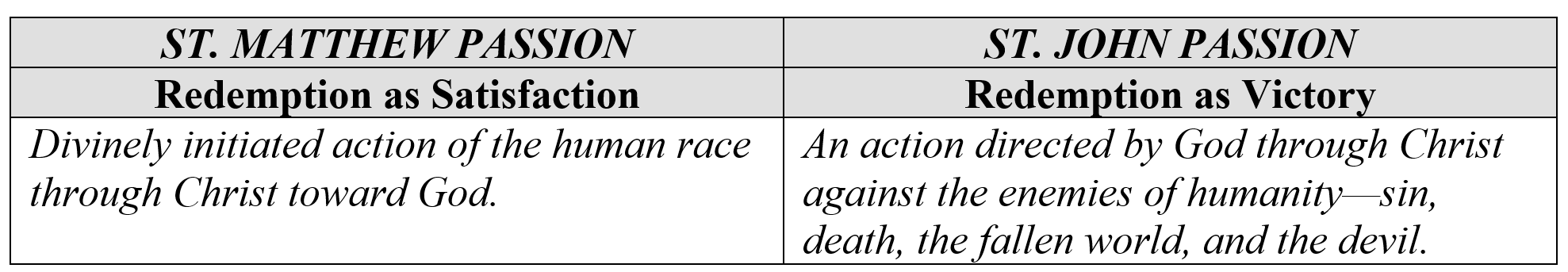

During this Lenten season as we celebrate Holy Week, we should consider the work of Bach in relation to the atoning death of Christ. You may be aware of different “pictures” or “models” of the atonement. As it turns out, the Christus Victor picture of the atonement is emphasized in The St. John Passion. By contrast, the Anselmian satisfaction/substitutionary model of the atonement is presented in his St. Matthew Passion.[2]

The St. Matthew Passion

The St. Matthew Passion begins with the weeping daughters of Jerusalem looking at the bridegroom, who is “like a Lamb [Als wie ein Lamm]” who bears our guilt (Schuld):

O pain! Here the anguished heart is trembling!

How he faints, how pale is his face!

The [eternal] Judge is bringing him before the judgment;

There is no solace, and no helper.

He is suffering all the tortures of hell,

Which he is to pay for someone else’s crime

[Er soll für fremden Raub bezahlen].

There is here a divine exchange, as Anselm puts it forth—the innocent Lamb for guilty humanity.

It is my sins for which Thou, Lord, must languish;

Yea, all the wrath, the woe, Thou dost inherit,

This I do merit.

Again,

What punishment so strange is suffered yonder!

The Shepherd dies for sheep that loved to wander;

The Master pays the debt His servants owe Him,

Who would not know him.[3]

The noted historian of theology Jaroslav Pelikan wrote: “Anselm’s Christ saves by his death, which, by virtue of his being both God and man in one person, renders a satisfaction to God that is both applicable to humanity and universally valid.”[4]

The eleventh-century theologian Anselm wrote Cur Deus Homo—“Why God Became Man.” He worked out the logic of the atonement in the following way: Human beings owe a debt to God that they cannot pay, but must pay it; God, who is owed the debt and can pay it, takes on human nature in the form of Christ so that, as man, he pays the debt that we owe; this Christ takes our place and offers compensation (“satisfaction”) to God as God on our behalf.[5] In his book The Cross of Christ, John Stott reflected on Anselm’s model, noting that the essence of sin is man substituting himself for God while the essence of salvation is God substituting himself for man.[6]

The St. John Passion

In the St. John Passion, there is much emphasis on the theme “It is finished [Es ist vollbracht]” which brings “rest for all afflicted spirits.” The theme throughout this Passion is redemption from the enemies of humankind. Furthermore, it is not the resurrection and empty tomb that Bach (following Luther) sees as ending “the strange and dreadful strife [wunderbarer Streit].” It is the cross—again Good Friday, not Easter—that brings about the reconciliation (2 Corinthians 5:19: “God was in Christ reconciling the world to Himself”).

Victorious Judah’s hero fights

And ends the strife [Kampf].

It is finished.

Bach stands against the Enlightenment rejection of a personal devil. Like Luther, Bach took Satan seriously. Despite death’s long-held tyranny, God is ultimately triumphant in Christ:

The wounding, nailing, crown and grave

The beating, which were there the Savior giv’n,

For him are now the signs of triumph [Seigeszeichen].

There are also cosmic upheavals to dramatize the cosmic battle:

My heart! See, all the world

Because of Jesus’ woe in woe is shrouded,

The sun in deepest mourning clouded.

The veil is rent, the rocks are cleft,

The earth doth quake, graves open flying,

When the Redeemer they see dying.

And so for thee, what wilt thou do?

Jesus is one who is in “prison [Gefängnis]” yet brings us freedom [Freiheit].” He took on “slavery [Knechtschaft]” for our “liberty [Freistatt].”

So here is what we have in chart form:

Pelikan declares that in composing the two passions with their two distinct, prominent atonement themes, Bach refused to choose from among alternatives that had equally legitimate authority in his tradition.[7]

These pictures of atonement, while not giving the fuller picture, remind us of what Christ came to accomplish. Bach emphasizes both that “the Son of Man did not come to be served but to serve and to give his life as a ransom for many” (Mark 10:45) and that “the Son of God appeared for this purpose, to destroy the works of the devil” (1 John 3:8).

I trust that, during this Lenten season and during Holy Week in particular, you will be drawn to the works of Johann Sebastian Bach—the musical genius and the Fifth Evangelist—and be drawn closer to Christ, the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world.

Notes

[1] BWV = Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis (Bach Works Catalogue)

[2] Here I draw on Jaroslav Pelikan, Bach Among the Theologians (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1986), chs. 7-8.

[3] The German text is:

Wie wunderbarlich ist doch diese Strafe!

Der Gute Hirte leidet für die Schafe;

Die Schuld bezahlt der Herre, der Gerechte,

Für seine Knechte!

[4] Pelikan, Bach, 101.

[5] See William Lane Craig’s discussion of Anselm’s view, which has been misunderstood (e.g., misunderstandings like “God requires punishment because he has been offended”; “this view of the atonement is informed by the image of a feudal lord”). Craig also argues that Anselm’s view needs more—namely, a robust penal substitution and imputation understanding, which the Reformers emphasized. Atonement and the Death of Christ (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2020), 183-88.

[6] The Cross of Christ (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1986), 160.

[7] Ibid., 115.

Paul Copan is the Pledger Family Chair of Philosophy and Ethics at Palm Beach Atlantic University. Learn more about Paul and his work at paulcopan.com.

image: Johann Sebastian Bach