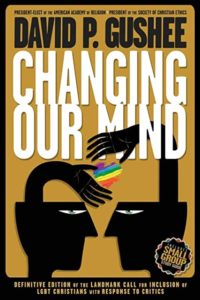

A thoughtful American sister recently asked what I thought of evangelical scholar David P. Gushee’s Changing Our Mind: Definitive 3rd Edition of the Landmark Call for Inclusion of LGBT Christians with Response to Critics (Canton, MI: Read the Spirit Books, 2017). I asked her if the book was well done—with over 1 million new books appearing every  year, we all need to be selective! She said Changing Our Mind is well worth reading, so I ordered it right away, and read it last week. And I am glad I did; this is an important work, if only because it is influential.

year, we all need to be selective! She said Changing Our Mind is well worth reading, so I ordered it right away, and read it last week. And I am glad I did; this is an important work, if only because it is influential.

Meanwhile, a friend dealing with LGBTQ issues in his own community emailed, mentioning Gushee and asking some pointed biblical questions. (Several of these I address in an interview with Guy Hammond, “Gay & Christian?”.) But after a few hours fleshing out my thinking on Gushee’s work, I stopped.

Who am I, after all? I’m not the most qualified to engage these issues, even though I’ve been an adviser for Strength in Weakness since its inception, and appreciate the seriousness and relevance of sexual issues in our day. Yet knowing when to “lateral” is an important and time-saving skill. So, remembering my friend Paul Copan, a great thinker who is both a philosopher and an ethicist, I asked him if he’d written anything in response to Gushee.

Lateraling himself, Paul told me he had a friend, George Guthrie [photo below L], who’d offered a thorough and balanced critique of Changing Our Mind. Better still, it turns out that Guthrie is a friend of Gushee—lending both credence and the personal element to his critique. I observe four degrees of separation: Gushee-Guthrie-Copan-Jacoby. This is also a chain of friendship: David and George are friends; George and Paul are friends; Paul and I are friends. Relationship is important if we're not to demonize or misrepresent others.

Guthrie’s critique appears at the website of The Gospel Coalition under Bible & Theology: Changing Our Mind” (January 9, 2015). (No—the review doesn’t precede the book! The bibliographic information above pertains to the first edition.) Click HERE for Guthrie’s response.

Guthrie’s critique appears at the website of The Gospel Coalition under Bible & Theology: Changing Our Mind” (January 9, 2015). (No—the review doesn’t precede the book! The bibliographic information above pertains to the first edition.) Click HERE for Guthrie’s response.

If you’re interested, following are some of my own thoughts in response to David Gushee. (But I think Guthrie’s response is better done than mine, so please don’t miss it!)

* * *

What DJ found helpful

There are many interesting and valuable points in Changing Our Mind. The following comments generally follow the page order of the 2017 edition. That is, the bullet points aren’t in order of importance.

- We can appreciate Gushee’s encouragement to seek discernment with both head and heart (p.54). This is an area in which I (continually) need to grow.

- He rightly points out the hypocrisy of evangelical churches who harp on homosexuality, but say little if anything about materialism, drunkenness, gluttony, and other behaviors / lifestyles endemic in their congregations (77). Surely we need to be consistent, and avoid favoritism.

- Further, Gushee loathes the “mutual consent” ethic (103), nor can he unreservedly embrace “welcome and affirmation” (104).

- He has relationships with family and friends who are gay and genuinely cares about them (115)—for David the topic is far from academic—and he touchingly offers a profound apology to those he’s hurt through his prior teaching (124).

- He also rightly reminds us of the higher percentage of LGBTQ homelessness because of rejection by their own families (136).

What DJ found unconvincing

![]()

Yet the book is uneven in the quality of its arguments, and many times I noted errors of fact or logic.

Yet the book is uneven in the quality of its arguments, and many times I noted errors of fact or logic.

- Gushee reasons that since most churches accepting divorcees, and remarriages, even if they aren’t biblically warranted, we should accept gay marriage (41). But the parallel isn’t close enough to count as evidence for his position. After all, some divorces are legitimate, others are not—the very point about marriage itself. If one teacher turns a blind eye to cheating in the classroom, that hardly means everyone else should.

- Paul states that homosexuals exchange what is natural for what is unnatural. Gushee points out that for homosexuals, homosexual activity would be natural, not unnatural (86). Those without normal heterosexual attraction are an exception; Rom 1 does not directly apply to them. But this will not work. Otherwise, it would be unnatural (and sinful) for a heterosexual to engage in homosexual acts. By the same token, a homosexual who married someone of the opposite gender and engaged sexually would be sinning, too. He/she should marry someone of the same sex. Paul’s concern is not the theoretical (and bizarre) behavior of someone who is oriented one way but acts in another. (That’s a rare event, in any case.) Of course biblically speaking, we are called to rise above the level of mere nature, to the spiritual. That means denying ourselves, not indulging ourselves (Luke 9:23).

- Speaking of Romans 1, throughout the book Gushee exaggerates the degree of scholarly dispute over the Greek term arsenokoites (56). Until very recently, the consensus of Greek scholars and commentators was that the terms in Leviticus and Romans referred to homosexual sin.

- Gushee repeatedly cites a figure of 3.4-5.0% for the LGBT population (92). Whether this too high or not isn’t my concern. To be fair, and biblical, and for a fuller-orbed picture sociologically, percentages for other "orientations" should be offered too—like anger (13%), gluttony (11%), and drunkenness (6%). My figures are just made up, yet such information might reveal homosexual temptation/sin not as unique, but in a more biblical light—one among many behaviors that are opposed to God's holiness. All of us are tempted. One person’s temptation to commit sin X may well be double the intensity of another’s homosexual temptations. Why should homosexuals get a free pass? We are called to holiness—to say no to sin (Titus 2:11-14)—not to follow our own path. Besides, God provides a way out (1 Cor 10:13).

- Yes, everyone’s sexuality is broken, and we now live in a Genesis 3 world (97). Yet in God’s kingdom, we return to God’s will and plan for our lives (Gen 1-2). Brokenness isn’t meant to be normative among God’s people, if this means that we condone or practice adultery, theft, murder, slander, etc. We are called to obey God, not follow our feelings (Jer 17:9; Prov 14:12).

- In chapter 17 David jumps too quickly to “paradigm shift,” which he illustrates with the Emmaus Road disciples and Peter in Joppa/Caesarea (Luke 24; Acts 10). Certainly he is correct that validation of the gay agenda—even with the restriction of sex to monogamous, covenantal unions—would constitute an enormous paradigm shift. Yet Gushee has not demonstrated that such a shift is supported scripturally. He has not satisfactorily dealt with the principal passages against homosexuality, nor has he offered a theology of sexuality in line with the principal passages supporting God’s original plan (traditional sexual mores).

- In chapter 20 the author compares the almost total renunciation of antisemitism (Gushee’s area of expertise) with a predicted endorsement of homosexuality (134). To be sure, there are some parallels. Yet antisemitism finds no biblical support—nor does homosexuality.

- Gushee claims that the Bible doesn’t condemn slavery (160), yet that is a selective reading. Slave traders are condemned in the New Testament (1 Tim 1:10), and in the Old Testament kidnapping is a capital offense (Exod 21:16; Deut 24:7). For more on slavery, click here.

- The parallel with Peter’s change of mind regarding Gentiles is interesting, and indeed the Lord did change Peter’s mind through relationship with real human beings (164), but the Jew-Gentile issue is frequently addressed in both testaments. God’s will on this matter is called a “mystery” (Rom 16:25; Eph 3:3-4, 6, 9; Col 1:26-27), but not because it was inscrutable. God’s plan to create a new people out of Jews and Gentiles is prophesied in the Old Testament and fulfilled in the new. Peter could have / should have known. How the Lord would expect anyone to conclude scripturally that he (now) accepts homosexuality and gay marriage is the real mystery.

- It is simply wrong to claim that 1 Pet 3:1-6 directs wives to remain in abusive marriages (166). There’s no doubt the passage has often been misused in such a way, but that interpretation hardly flows from the text itself.

- Yes, we need to stop treating gays with contempt (171), but it doesn’t follow that doctrinal change is required before we can love them (that we must accept a gay agenda).

Final thoughts

Our author advocates “Celibacy outside of lifetime covenantal marriage, monogamous fidelity within lifetime covenantal marriage” (142), whether in a heterosexual union or a homosexual one. For Gushee, rejecting monogamous homosexual covenantal marriage is equivalent to rejecting homosexuals as people. Yet plenty of Christians love their gay friends or family members, yet without accepting Gushee’s notion that homosexual marriage is pleasing in God’s eyes as long as it is “covenantal” and “monogamous.”

He seems to admit that the case for homosexuality is weak, and is refuted by six texts (the so-called “clobber passages”) (154). This reminds me of my 2020 debate on baptism with Baptist scholar Thomas Ross. Thomas asked me if I could still make my case if the six most convincing baptism texts were removed from the New Testament—a sort of tacit admission of the weakness of his own case.

“Therefore, it simply is a violation of my own hermeneutic to read six passages that might speak negatively about some version of same-sex activity in some remote historical context apart from the broader moral framework provided by this Jesus. And this Jesus inevitably broadens the LGBTW issue out from merely being about who can have sex with whom to how vulnerable people should be treated, a key question for both the prophets and Jesus” (156). But the Old Testament was Jesus’s Bible. Why should we think that Jesus rejected the normative Jewish understanding of the scriptures regulating sexual activity? Although some of his reasoning is flawed, I believe it’s fair to say that readers may be distracted from the key biblical texts by his skillful storytelling and personal anecdotes. These are of course welcome, but the validity of his embrace of gay marriage should depend on scripture, not simply anecdote and emotion (head and heart).

As Guthrie rightly observes, “David shapes his argument by weaving a consideration of biblical texts, moral reasoning, and, above all, the evoking of personal stories. It’s important to attend not only to what he argues but how he does so. In many ways, the stories form the foundation of his paradigm shift—with Scripture and reason being reconsidered in light of those stories. We’ll dig down to that foundation by working our way through David’s approach to the Bible and his ethical arguments.”

Last, maybe the problem isn’t caused by inconsistent practice of church discipline—although Gushee’s point about our hypocrisy in policing for one sin but not for another is well taken. I rather suspect our standards are too low to begin with—all around. 1 Corinthians 5 is an ignored passage in evangelical churches. Preachers should preach on all sins, and church members as a body should enforce the expectation of holiness in their own lives and in the fellowship.

Anyway, you have my thoughts above, and don’t forget George Guthrie’s valuable critique.