|

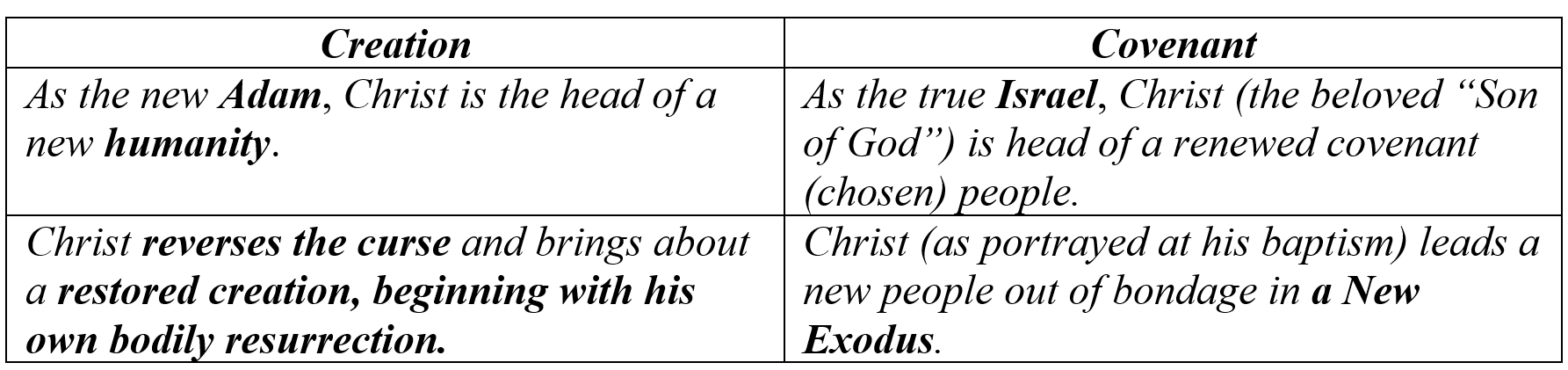

One often-unsung stanza from Charles Wesley’s hymn “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing” is this one: Come, Desire of nations, come! Fix in us Thy humble home: Rise, the woman’s conqu’ring seed, Bruise in us the serpent’s head; Adam’s likeness now efface, Stamp Thine image in its place: Final Adam from above, Reinstate us in Thy love. Charles’ brother John Wesley is known for his theology of Christian perfection, drawn from passages such as Matthew 5:48 (being perfect like God ) and 2 Peter 1:4 (being partakers of the divine nature). Charles likewise held to a variation on this theme. Both Wesleys drew on the long-standing tradition of deification or theosis, located most notably in the Eastern Orthodox tradition. We can find this doctrine of deification in Roman Catholicism as well. Does Protestantism have any share in this tradition? As it turns out, yes it does. “That We Might Become God”? Going back to the fourth century, we see this kind of language in a leading defender of Christian orthodoxy, Athanasius. In his de Incarnatione, he affirmed: “For the Son of God became man so that we might become God.”[1] Even Protestants have used this language to talk about sanctification. Of course, the doctrine of deification isn’t anything like Mormonism, which breaks down the Creator-creature distinction—a glaring heresy. For example, Lorenzo Snow, the fifth Latter Day Saints president, declared: “As man is, God once was; and as God is, man may become.” Within the bounds of orthodoxy, Christian deification has to do with participating in the divine life through God’s gracious gift so that we, by the Spirit, may become conformed to the image of Christ (2 Corinthians 3:18; 4:4-6; Galatians 4:19; etc.). As we look into our Protestant theological sideview mirrors, this doctrine of deification may be closer than it appears. There is a biblical theology behind it. Because humans bear the image of God, we are equipped to rule creation with God (Genesis 1:26-28; Psalm 8) and to walk with/worship God, just as Adam and Eve did in the temple sanctuary of Eden (Genesis 3:8). God made humans to be priest-kings to fully live out the divine image—as co-regents with God and as worshiping priests in his presence. Our earliest ancestors failed to fulfill this vocation. After the exodus when God called his son Israel out of Egypt (Hosea 11:1), God made a covenant with them at Sinai. God called them to be a kingdom of priests (Exodus 19:6). The nation of Israel, however, ended up failing, proving to be a disobedient son (Isaiah 1:2-3; 30:9; Mal. 1:6). In the fullness of time, Jesus of Nazareth enters into this theodrama in human history. He faithfully lived out Adam’s and Israel’s story. He is the new Adam—the leader of a new humanity who ushers in a new creation through his resurrection (the eighth day of creation, as Irenaeus called it). He was also the true Israel—the faithful and well-pleasing Son (Mark 1:11) to lead a new covenant community through a second exodus and to inaugurate a new covenant with people from every tribe, tongue, people and nation. So, he successfully lived out Adam’s and Israel’s story. He came to restore creation and to lead his people out of bondage to sin and Satan in a new exodus so that we might no longer be slaves to sin (Romans 6).[2] In Christ, God is doing a great work to restore and rebuild his fallen creation and restore us to something glorious—something that must be achieved by divine grace rather than human self-effort. As the hymnwriter Joseph Hart wrote: Come, ye weary, heavy laden, Lost and ruined by the fall; If you tarry till you’re better, You will never come at all. Protestants and Theosis Whether or not we apply the term theosis to ourselves, keep in mind that this doctrine in some form is affirmed by a goodly array of influential Protestant thinkers. Theologian and biblical scholar Michael Reardon and I are coediting a forthcoming volume with IVP Academic entitled “Transformed into the Same Image”: New Investigations into the Doctrine of Deification. In it, various scholars like Alister McGrath, Robert Garcia, Ben Blackwell, and others explore how noted Protestants have appropriated the doctrine of deification: Martin Luther, John Calvin, Jonathan Edwards, John and Charles Wesley, C.S. Lewis, the sometimes-misunderstood Witness Lee,[3] and so on. Consider Luther, who was as good a Protestant as any. He followed the logic and language of Athanasius in a 1526 sermon:

In another sermon (1525), Luther wrote:

Whatever we may think of the term “deification” or being “divinized,” Jesus Christ came into the world to bring about a transforming work in us. He came to save us from our sins, and it is his goal that his image would be stamped upon us. As Paul wrote to the Galatians, “My children, with whom I am again in labor until Christ is formed in you…” (Gal. 4:19). May we during this Christmas season consider not just the celebration of the entrance of a great Savior into the world, but also the transformative work he desires to do in each of us—a grand and glorious work indeed! Let us think more deeply about what it means to be filled up to all the fullness of God (Ephesians 3:19). You may not use the term divinization or theosis, but let us consider what it means to “become partakers of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4). To that end, let me finish with a few stanzas from various Charles Wesley hymns that we may ponder…. “Since the Son Hath Made Me Free” reflects this doctrine of theosis: Heavenly Adam, life divine, Change my nature into thine; Move and spread throughout my soul, Actuate and fill the whole; Be it I no longer now Living in the flesh, but thou. “Let Heaven and Earth Combine”: He deigns in flesh to appear, Widest extremes to join; To bring our vileness near, And make us all divine: And we the life of God shall know, For God is manifest below. “All-Wise, All-Good, Almighty Lord”: Didst thou not in thy person join The natures human and divine, That God and man might be Henceforth inseparably one? Haste then, and make thy nature known Incarnated in me. Notes [1] Athanasius, de Incarnatione 54.3. [2] See N.T. Wright, Paul (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2005). [3] See the Christian Research Journal issue “We Were Wrong” (vol 36, no. 6, 2009), which was devoted to reversing its judgment on Witness Lee, affirming him as orthodox and repudiating its earlier charges of heterodoxy against him: https://www.equip.org/christian-research-journal/we-were-wrong-2/. — Paul Copan is the Pledger Family Chair of Philosophy and Ethics at Palm Beach Atlantic University. Learn more about Paul and his work at paulcopan.com. |